Post by Fuggle on May 7, 2007 15:01:05 GMT -5

THE GREATEST ROCK'N'ROLL STARS

"Except the Eagles, the Eagles are better than us."

It's a sad thing when artists disown some of their greatest and most representative work. Anyone who remembers the heady days of Britpop will recall the peak of the Blur/Oasis Wars, when "Country House" and "Roll With It" were released in the same week and went head-to-head for the No.1 spot, absurdly provoking lengthy and serious stories on News At Ten, and putting pop music at the forefront of the nation's cultural consciousness in a way that hadn't happened since acid house in the late 1980s and wouldn't come close to happening again until the dark horrors of Pop Idol.

While their careers subsequently took very different directions, Blur won the only battle between the two bands that counted for anything, and they won it because they deserved to. "Country House" is a genius pop single, hiding bleak, melancholy lyrics about psychological collapse and depression behind an irresistible jaunty hornpipe of a tune and a gaily-coloured Benny Hill-style video full of Page Three girls in bikinis. (Not until Outkast's majestic "Hey Ya" would there again be such a discrepancy between a song's words and its sound.) Meanwhile, "Roll With It" is Oasis at their absolute worst - vacuous drivel both musically and lyrically, a sub-Status Quo stodgy lump of a tune married to meaningless words that recall the yuppie-era nadir of Wham! - a "Young Guns (Go For It!)" for the mid-90s weekend-scally crowd. This reporter can't even remember what the video was about, but feels fairly safe in hazarding a guess at some kind of grunting "keeping it real" pseudo-live performance footage in deliberate contrast to Blur's camp middle-class art-school archness.

Chastened at their defeat by the effete, Oasis subsequently went on to produce their best work, the overblown coke-fuelled epic of "Be Here Now". Here was the swagger of early songs like "Supersonic" and "Rock'n'Roll Star" finally backed up with music that sounded massive enough to carry all their outlandish boasts, and all-powerful enough to sweep the world's stadiums and mega-arenas before it. While half of the album is self-indulgent tripe (one of the first effects of cocaine being to rob the user of the ability for critical self-analysis and astute editorial judgement), the half that's left contains songs that sound bigger than planets, with lyrics full of intoxicating belief. The shameless "Hey Jude" ripoff/update of "All Around The World", the driving, spine-tingling "I Hope, I Think, I Know" and the colossal seven-minutes-long-and-you-wish-it-was-ten of "It's Getting Better, Man!!" - all are the sound of a band balancing briefly on the highest wire, the tightrope stretched between the supporting pillars of creative productivity and commercial success.

(From that short-lived point, it's an inevitability that the heavy weight of shedfuls of cash bulging in their pockets and the fat-saturated flab of decadent living will make the wire sag in the middle, the band standing precariously at the centre of it sinking lower and lower until all the tension is gone and the slope is so steep and wobbly it's impossible to climb back up to either end - though it rarely plunges so low so quickly as "Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants" - but let's put this metaphor out of its misery quickly and move on.)

Anyway, this article isn't about Blur or Oasis. The point is that by just a couple of years later, both bands had disowned some of their finest works. Noel Gallagher apologised for the grandeur and limitless ambition of "Be Here Now", blaming it all on the cocaine like some penitent junkie on a 12-step program surrendering responsibility for his own choices and desires; Blur winced at all mention of "Country House" as they ducked out of the mainstream chart battle and pursued more "intellectual" critical acclaim with discordant, "difficult" anti-pop albums like "13" and the eponymous "Blur". And that, if you were wondering where all this was going, is what brings us to The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle.

The Sex Pistols happened 28 years ago (no, really - check the arithmetic yourself), in the unfamiliar and - to anyone who wasn't there at the time - unimaginable pre-Thatcherism world of 1976. History gets distorted over such long periods, by any number of factors whether egotistical, political, legal or just plain forgetful, but received wisdom has arrived at the conclusion that the band is best defined by its sole studio album, "Never Mind The Bollocks", and by the historical revisionism/record-straightening (either or both, depending on your viewpoint) of 2000's documentary movie "The Filth And The Fury". But in truth, and despite what Mojo and Q and Uncut would have you believe, the era of the Pistols is most accurately represented by a different movie, and, especially, by its soundtrack album.

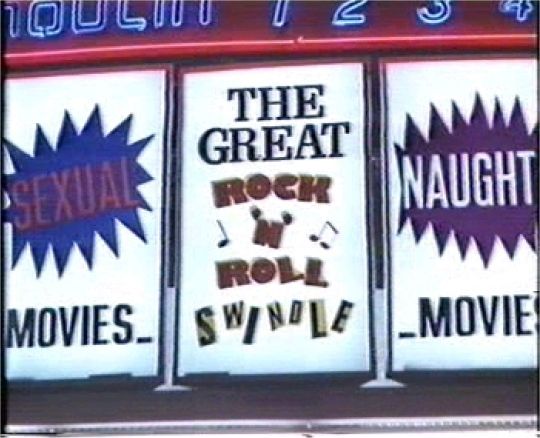

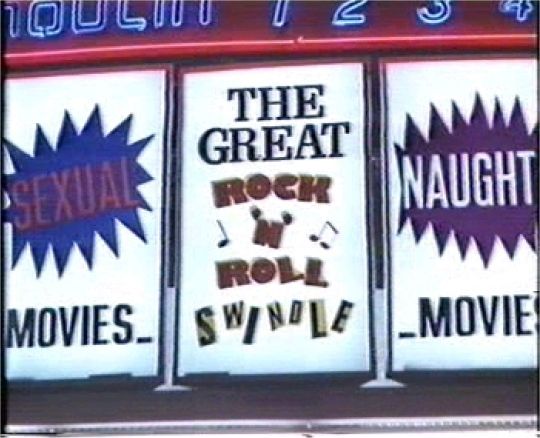

"The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle" was released in 1979, by which time punk's brief period as an active cultural force was already over. Nowadays the film is widely regarded as a self-publicising, self-glorifying cash-in vehicle for the Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren, which it undoubtedly is. But it's also dismissed as a factless fantasy portrayal of the Pistols' turbulent career, which is a rather more disingenuous criticism motivated by some dishonest vested interests, and as being devoid of artistic merit, which is just plain wrong. And so, World Of Stuart is taking it upon itself to begin the critical rehabilitation of a movie and an album which in many respects depict the punk era and particularly the story of the Sex Pistols the way it really was, and aside from that are tremendous, thought-provoking and ahead-of-their time entertainment and culture, sometimes intentionally and sometimes by accident. Let's see if we can convince you. It may take some time.

It's in the interests of the "grown-up" music press to present the punk era as a perfect, heroic crusade, because it's easier to mythologise it that way and sanitised mythology makes readers feel good about themselves and shifts magazines. But even someone who, like your reporter, was only 10 at the time knows it didn't actually happen that way. Punk was a much messier business than that, sometimes highly questionable in both action and motivation, and "The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle", with its potent and haphazard mixture of fact and fiction, sincerity and exploitation, iconography and pornography, is a much more accurate and true picture of the times.

The closing part of the movie in particular - portraying the time immediately after the band's break-up in America when McLaren contrived to get Johnny Rotten fired, and Pistols guitarist and drummer Steve Jones and Paul Cook fly off to Brazil to frolic in the surf with Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs and - supposedly - Nazi fugitive Martin Bormann, while junkie bass-idiot Sid Vicious wanders the streets of Paris in a swastika t-shirt assaulting prostitutes, is emptily unpleasant viewing without any kind of redeeming qualities.

But then, not to show such things would be to deny the reality of punk, where early use of Nazi imagery by the fashionista-intellectual sorts who started the movement was designed to shock but also make a valid political statement, but was then brainlessly adopted by cretins like the right-wing skinhead gangs who used to plague Sham 69 gigs. As with any culture that grows into something big, morons join in along with everyone else and distort the original meaning. (An observation made again in Nirvana's "In Bloom" 20 years later, and by Robbie Williams roughly every other single.)

It's highly doubtful, of course, whether the film has even the remotest intention to make this point, but accidental meaning is a theme that crops up in "The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle" time and again. Almost three decades of hindsight lends the film a contemporary relevance and resonance that was almost certainly never intended by its makers. It starts, for example, with a Pop Idol-esque audition for a replacement singer for Rotten ("Kids Audition -Anyone Can Be A Sex Pistol", runs the billing) which was probably meant to be absurdly satirical rather than ending up as the most frighteningly prescient picture of the future since Orwell's "1984", but which is no less powerful for that.

But then, at the same time, the film also mimics quintessentially British culture like the gentle Ealing comedies, with veteran comic actresses like Irene Handl and 70s porn star Mary Millington lending their talents to segments that imply the entire film is tongue-in-cheek post-modern (before anyone had even heard of "post-modern") self-mockery, a music-hall farce that's personified by Steve Jones' playing of the central "character" in what passes for the movie's binding narrative. A natural actor (a bit like his namesake Vinnie would turn out to be decades later), Jones hams up his role as a leather-trenchcoated gumshoe with deadpan wit that seems to debunk any notion of the movie being taken seriously. (And just to reinforce that view - it is, let's not forget, a musical. The story of the most subversive cultural phenomenon since the Tolpuddle Martyrs is a musical.)

And there are also genuinely documentary elements to the film, with clips of real events (like the extraordinary scenes when a crowd of hymn-singing locals picketed outside a Pistols gig in Caerphilly, Wales) and interviews with real figures from the story - record company executives, local councillors and so on - which cast light on things from an angle widely ignored in the rewritten modern history of punk. McLaren's careful cutting of these clips to assist in his own particular telling of the tale means you always need to keep a big pinch of salt handy with relation to the context and chronology, but much of the footage manages to stand on its own merits and speak for itself.

Swindle can't decide all the way through whether it's trying to present a polemic on behalf of McLaren's "I am the master manipulator who cleverly meant it to happen this way all along" hijacking of reality, or just take the piss, and the struggle between the two conflicting sides - mirroring, probably unintentionally, the conflict at the core of the Pistols between Rotten's serious-minded cultural-revolutionary politics and Jones and Cook's "We're only here for the birds and beer" perspective - is all the more fascinating for it.

So that's the movie - a messy but always-watchable tangle of reality and fantasy, insult to history and insight into it at the same time, never to be taken at face value but nevertheless containing plenty of truth for the attentive viewer who can be bothered to look for it. What about the album? The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle soundtrack is a record that's almost never afforded any merit or significance at all when looking back at the legacy of the Sex Pistols, but it actually contains some of the most telling and candid representations of their existence, as well as pointers to the futures of the various protagonists.

Tracks like "Lonely Boy" and "Silly Thing", for example, while credited to the Pistols, are clearly the prototypes for the work of The Professionals, the band formed by Cook and Jones after the last remnants of the Pistols finally dissolved some time after the initial breakup. (Increasingly desperate cash-in "Sex Pistols" records, such as the posthumously-released Sid Vicious covers of 50s rock standards "C'mon Everybody" and "Something Else" and Ronnie Biggs' "No-one Is Innocent", continued to appear in a steady stream for years after the band disintegrated on stage at the Winterland in San Francisco at the end of their American tour in January 1978.) The Professionals (and the aforementioned Swindle tracks) pioneered a curious kind of "sensitive yob" rock, combining the trademark heavy Pistols sound with melancholy, regretful lyrics and singalong football-crowd choruses, which enjoyed minor chart success with great singles like "1-2-3", "Just Another Dream" and "Kick Down The Doors" but couldn't sustain the band beyond a patchy second LP in 1981.

And McLaren's own numbers, including orchestral takes on "EMI" and "God Save The Queen" (the latter of which he uses, via a whispered voiceover, to introduce the Fagin-esque character he attempts to portray himself as in the movie and set out the idea of "The Swindle" itself) and a rendition of music-hall standard "You Need Hands" (made famous by Max Bygraves) foreshadowed the eclectic directions he would go on to take in later years, touching on everything from the urban dance music of Soweto to the oddly moving opera-based single "Madam Butterfly". But in these five songs of McLaren, Cook and Jones (out of the album's 24) we've still only heard a fraction of Swindle's all-encompassing scope.

In addition to Cook and Jones' yob rock and McLaren's classical/theatrical dabblings, the album also reflects the movie's random balance between the whimsical and the unsavoury, featuring the contributions of Ronnie Biggs and "Martin Bormann", with the latter singing on one of two versions of the ugly, morally-ambiguous "Belsen Was A Gas" (Sid Vicious' only recorded songwriting credit in the band, and which in the hands of Rotten sounded like an anti-war anthem, but rather different coming supposedly from a Nazi war criminal with new lyrics). But there's also a couple of cartoon-punk numbers from Eddie Tenpole (later to form New Romantic village idiots Tenpole Tudor of "Swords Of A Thousand Men" fame) in the form of "Who Killed Bambi?" and a silly cover of "Rock Around The Clock".

(It's worth diverging momentarily at this point to note that "Who Killed Bambi?" was the movie's original title, and work had actually been started on filming a very different script - written, faintly amazingly, by the now-famous US movie critic Roger Ebert - before it became Swindle. All there was to show for the first £75,000 spent by McLaren and original director Russ "Valley Of The Dolls" Meyer was a sequence showing the nasty, and real, cold-blooded killing of a baby deer in a Welsh forest, which adorns the album's back cover lying dead in a pile of autumn leaves from a bloodstained crossbow-dart wound in its throat. Curiously, an unrelated French movie of the same title was released in 2003.)

We also get all three of Vicious' crude but entertaining solo efforts, including his valedictory yowl through "My Way". But in the eyes of the public the Sex Pistols were still synonymous with their frontman, and for the album to have any credibility as a Sex Pistols release McLaren needed to have a substantial presence from Rotten on it. Unfortunately for him, by 1979 the relationship between the manager and the former singer was poisoned beyond rescue (as indeed it remains to this day), and McLaren had to resort to desperate measures, tacking a load of cursory, slapdash 60s-rock covers recorded early in the Pistols career for B-sides onto the tracklisting, along with a version of "Anarchy In The UK" and a rehearsal-room tape that inadvertently provides Swindle's most affecting moment.

Forming the second and third tracks on the album, the recording has the Pistols (in the form of Rotten, Cook and Jones - who, if anyone, is playing bass guitar is unknown, but it doesn't seem to be either the inept Vicious or original, sacked, bassist Glen Matlock) messing around half-arsedly in the studio playing a cover of Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode". Rotten gets four tuneless, off-key words into the song before screwing it up ("If you could seeee... oh God, fuck off") but ploughs through the first verse before muttering "I dunno the words" and descending into improvised scat gibberish instead. This semi-entertains the singer for another minute or so before he complains "Stop it, it's fucking awful" and suggests they play "Road Runner" instead. The band segue without pausing into the classic Jonathan Richman number (giving the lie to McLaren's claims throughout the movie that they couldn't play), until Rotten laughs that he doesn't know the words to that one either.

But the others keep playing, and Rotten does his best around what lyrics he does know, seemingly just for something to do to relieve the monotony of this pointless busy-work exercise. No-one has ever sounded less convincing singing the words "Felt in touch with the modern world, fell in love with the modern world". Moments afterwards Rotten improvises the line "So cold here in the dark... with 50,000 watts of power", and the good-vibes driving song suddenly takes on an air of unfamiliar poignant melancholy.

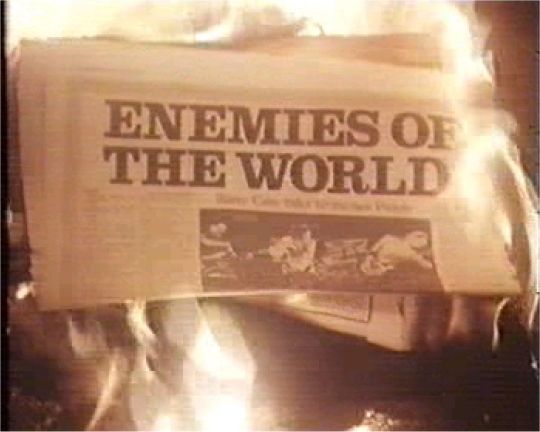

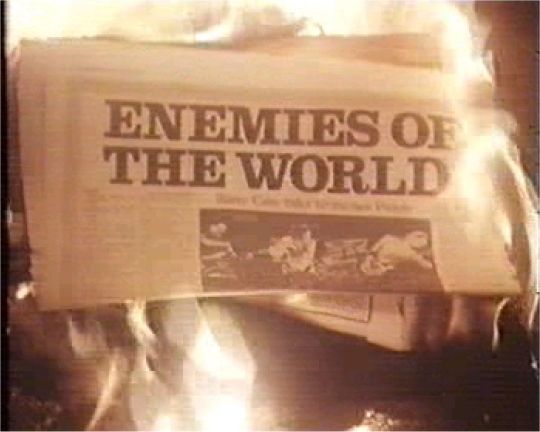

This was a band being vilified in the entire world's press, physically attacked in the streets (McLaren's faux-Machiavellian recounting in the movie of his glee at Rotten being slashed by a gang of thugs outside a pub and Cook being beaten up and stabbed by a crowd in a tube station is one of the film's most genuinely distasteful parts), and generally presented as unspeakable evil Antichrists threatening the destruction of society as we know it, yet here they're revealed as a bored, ordinary and isolated bunch of young men aimlessly killing time in a grubby windowless room while other people manipulate their lives into a hideous mess, their famed and supposedly world-shattering music seemingly powerless to help them.

Dejectedly, the singer continues to bemoan the situation ("Road runner, road runner...oh God, I don't know it, it's fucking ridicularse... wish I had the words") as the others continue doggedly on. As Rotten appears to give up entirely, the band build the song up to a climax, a crash of Cook's cymbals seems to fire the singer to one last effort and he suddenly throws his heart into it just when it seems hopeless - "...runner, Road RUNNER" and suddenly it's the old familiar Rotten, spitting life and bile into these most easy-going of lyrics and summoning up everything he can pull together to try to give this bleak situation some meaning and purpose. It only lasts about 20 thrilling seconds, as the singer's lack of command of the words leaves him with nowhere to go and the song stumbles to an untidy close, but for those few seconds "Road Runner" is nothing less than a shining demonstration of the magical capabilities of music, as a room full of people who don't like each other, stuck in a miserable situation to produce a filler track on a cynical cash-in album, somehow combine to make something that's an uplifting affirmation of the uniqueness of humanity and its capacity to create works of power and beauty at the unlikeliest moments.

Immediately after this, we get another of the album's many musical highpoints, in the form of the Black Arabs' eponymous disco medley. Funky wah-wah guitar and a throbbing hi-energy beat underpin a Boney M-style melding of "Anarchy", "God Save The Queen", "Pretty Vacant" and, oddly, Biggs' "No-one Is Innocent" - the lack of distinction between the "real" Pistols and the cash-in circus redolent of Swindle's kitchen-sink philosophy.

But even now we're not done with digging gems out of the album's random car-boot-sale collection of passingly-Sex-Pistols-related music. After some more Rotten covers and Cook and Jones numbers, we get a French-busker-with-accordion rendition of "Anarchie Pour l'UK" which shows what a great tune it is even when stripped of the Pistols' distinctive sonic assault. (This is a point, incidentally, that's also illustrated by many subsequent covers by various artists, including a lovely Waterboys-like acoustic version on the little-known "The Swindle Continues" album released by former Pistols soundman Dave Goodman, supposedly in collaboration with Cook and Jones, in 1988.) It also sounds a lot better when heard on the album, removed from the scenes of Vicious acting like an ignorant cretin in Paris which it's used to soundtrack in the movie.

And then, after a five-track Vicious/"Bormann"/Biggs cabaret interlude, and McLaren's orchestral, self-voiced reinterpretation of "EMI", it's time for the theme song.

"The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle" itself, written by Cook and Jones with the movie's director Julian Temple and sung by Eddie Tenpole and a load of singer-audition hopefuls, is one of the great unacclaimed punk singles. Setting out its stall immediately with the opening couplet "People said we couldn't play, they called us foul-mouthed yobs/But the only notes that really count are the ones that come in wads", this is a theme song in the most literal sense, summarising the movie's plot and the band's history in three slogan-strewn minutes of gloating about all the money McLaren has (supposedly) deliberately and cunningly embezzled from the music business, before Tenpole embarks on an extended and improvised libellous attack on various rock dinosaurs and punk contemporaries - Elvis Presley ("Died in 1959"), Chuck Berry, Ian Dury ("Cockney fraud"), Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan ("A parking ticket stuck to his arsehole"), Rod Stewart - and then the members of the Pistols themselves ("Sid Vicious, rock'n'roll clich-eye") over the triumphant guitar chords and the joyous refrain of the chorus line.

Eventually Tenpole dissolves into incoherent ranting and the wannabe Sex Pistols Idols come back in, chanting "Rock'n'roll swindle" in turn until the song judders to a close. The last hopeful sneers "Swindle - it's a swindle!" as the final note dies away - an ironic echo, intended or not, of Rotten's "Ever get the feeling you've been cheated?" parting shot from the stage at the end of the Pistols' ill-fated gig at Winterland. (It may or may not be by chance that the track follows close on the heels of Vicious' "My Way", which features parting shots of another kind.)

It's a thrilling conclusion, but such a neat ending would be out of keeping with the tone and spirit of the rest of the album and movie, so we get McLaren's wildly-misplaced "You Need Hands" before the album's actual closing track, "Friggin' In The Riggin'", a traditional old salty sea shanty appropriated by Steve Jones with even fouler lyrics than usual and used to soundtrack the film's end/credits sequence which depicts the Pistols once again in cartoon form as the crew of a becalmed, but then increasingly storm-tossed, pirate ship, deserted by one member after another until only McLaren remains, saluting with a smile at the mast as the ship sinks beneath the waves and the song fades out to its cheerfully-nihilist refrain (Friggin' in the riggin', there was fuck-all else to do").

There's one last twist, though, as this "happy ending" for the album gives way in the film to a montage of newspaper clippings reporting Vicious' death from a heroin overdose while on bail for the alleged knife murder of his girlfriend Nancy Spungen in New York's Chelsea Hotel, the montage soundtracked only by the desolate squawking of a few unseen seagulls. The injection of such a sour note at the end, the movie clashing awkwardly with its own soundtrack, is typical of Swindle: a schizophrenic, amoral mess of a venture whose moments of redemption seem as deliberate - and simultaneously as incidental and unplanned - as its moments of crass offensiveness and cynical, one-sided character assassination.

In a world where spin-doctors, concentrated media ownership, the erosion of civil liberties in the name of fighting "terrorism", the cult of celebrity and 24-hour news analysis rob us of the opportunity to interpret events or culture for ourselves, Swindle's shrugged-shoulders confusion of morality forces the viewer/listener to actually think for themselves about what's being presented to them. It's a habit that's being gradually discouraged in 21st-Century society, and anything that helps to hold back that tide should be cherished and protected.

The movie works best when viewed in the context of the whole of the Sex Pistols history - particularly "The Filth And The Fury", which is seen by some as Julian Temple's apology to the band for their portrayal in Swindle - but stands up in its own right too, both as documentary (though not in the way McLaren intended it) and entertainment. For anyone to whom punk is some distant, abstract thing that happened before they were born, it's actually a pretty decent depiction of the atmosphere of the time (from the cultural, rather than political, perspective at least).

"Except the Eagles, the Eagles are better than us."

It's a sad thing when artists disown some of their greatest and most representative work. Anyone who remembers the heady days of Britpop will recall the peak of the Blur/Oasis Wars, when "Country House" and "Roll With It" were released in the same week and went head-to-head for the No.1 spot, absurdly provoking lengthy and serious stories on News At Ten, and putting pop music at the forefront of the nation's cultural consciousness in a way that hadn't happened since acid house in the late 1980s and wouldn't come close to happening again until the dark horrors of Pop Idol.

While their careers subsequently took very different directions, Blur won the only battle between the two bands that counted for anything, and they won it because they deserved to. "Country House" is a genius pop single, hiding bleak, melancholy lyrics about psychological collapse and depression behind an irresistible jaunty hornpipe of a tune and a gaily-coloured Benny Hill-style video full of Page Three girls in bikinis. (Not until Outkast's majestic "Hey Ya" would there again be such a discrepancy between a song's words and its sound.) Meanwhile, "Roll With It" is Oasis at their absolute worst - vacuous drivel both musically and lyrically, a sub-Status Quo stodgy lump of a tune married to meaningless words that recall the yuppie-era nadir of Wham! - a "Young Guns (Go For It!)" for the mid-90s weekend-scally crowd. This reporter can't even remember what the video was about, but feels fairly safe in hazarding a guess at some kind of grunting "keeping it real" pseudo-live performance footage in deliberate contrast to Blur's camp middle-class art-school archness.

Chastened at their defeat by the effete, Oasis subsequently went on to produce their best work, the overblown coke-fuelled epic of "Be Here Now". Here was the swagger of early songs like "Supersonic" and "Rock'n'Roll Star" finally backed up with music that sounded massive enough to carry all their outlandish boasts, and all-powerful enough to sweep the world's stadiums and mega-arenas before it. While half of the album is self-indulgent tripe (one of the first effects of cocaine being to rob the user of the ability for critical self-analysis and astute editorial judgement), the half that's left contains songs that sound bigger than planets, with lyrics full of intoxicating belief. The shameless "Hey Jude" ripoff/update of "All Around The World", the driving, spine-tingling "I Hope, I Think, I Know" and the colossal seven-minutes-long-and-you-wish-it-was-ten of "It's Getting Better, Man!!" - all are the sound of a band balancing briefly on the highest wire, the tightrope stretched between the supporting pillars of creative productivity and commercial success.

(From that short-lived point, it's an inevitability that the heavy weight of shedfuls of cash bulging in their pockets and the fat-saturated flab of decadent living will make the wire sag in the middle, the band standing precariously at the centre of it sinking lower and lower until all the tension is gone and the slope is so steep and wobbly it's impossible to climb back up to either end - though it rarely plunges so low so quickly as "Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants" - but let's put this metaphor out of its misery quickly and move on.)

Anyway, this article isn't about Blur or Oasis. The point is that by just a couple of years later, both bands had disowned some of their finest works. Noel Gallagher apologised for the grandeur and limitless ambition of "Be Here Now", blaming it all on the cocaine like some penitent junkie on a 12-step program surrendering responsibility for his own choices and desires; Blur winced at all mention of "Country House" as they ducked out of the mainstream chart battle and pursued more "intellectual" critical acclaim with discordant, "difficult" anti-pop albums like "13" and the eponymous "Blur". And that, if you were wondering where all this was going, is what brings us to The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle.

The Sex Pistols happened 28 years ago (no, really - check the arithmetic yourself), in the unfamiliar and - to anyone who wasn't there at the time - unimaginable pre-Thatcherism world of 1976. History gets distorted over such long periods, by any number of factors whether egotistical, political, legal or just plain forgetful, but received wisdom has arrived at the conclusion that the band is best defined by its sole studio album, "Never Mind The Bollocks", and by the historical revisionism/record-straightening (either or both, depending on your viewpoint) of 2000's documentary movie "The Filth And The Fury". But in truth, and despite what Mojo and Q and Uncut would have you believe, the era of the Pistols is most accurately represented by a different movie, and, especially, by its soundtrack album.

"The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle" was released in 1979, by which time punk's brief period as an active cultural force was already over. Nowadays the film is widely regarded as a self-publicising, self-glorifying cash-in vehicle for the Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren, which it undoubtedly is. But it's also dismissed as a factless fantasy portrayal of the Pistols' turbulent career, which is a rather more disingenuous criticism motivated by some dishonest vested interests, and as being devoid of artistic merit, which is just plain wrong. And so, World Of Stuart is taking it upon itself to begin the critical rehabilitation of a movie and an album which in many respects depict the punk era and particularly the story of the Sex Pistols the way it really was, and aside from that are tremendous, thought-provoking and ahead-of-their time entertainment and culture, sometimes intentionally and sometimes by accident. Let's see if we can convince you. It may take some time.

It's in the interests of the "grown-up" music press to present the punk era as a perfect, heroic crusade, because it's easier to mythologise it that way and sanitised mythology makes readers feel good about themselves and shifts magazines. But even someone who, like your reporter, was only 10 at the time knows it didn't actually happen that way. Punk was a much messier business than that, sometimes highly questionable in both action and motivation, and "The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle", with its potent and haphazard mixture of fact and fiction, sincerity and exploitation, iconography and pornography, is a much more accurate and true picture of the times.

The closing part of the movie in particular - portraying the time immediately after the band's break-up in America when McLaren contrived to get Johnny Rotten fired, and Pistols guitarist and drummer Steve Jones and Paul Cook fly off to Brazil to frolic in the surf with Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs and - supposedly - Nazi fugitive Martin Bormann, while junkie bass-idiot Sid Vicious wanders the streets of Paris in a swastika t-shirt assaulting prostitutes, is emptily unpleasant viewing without any kind of redeeming qualities.

But then, not to show such things would be to deny the reality of punk, where early use of Nazi imagery by the fashionista-intellectual sorts who started the movement was designed to shock but also make a valid political statement, but was then brainlessly adopted by cretins like the right-wing skinhead gangs who used to plague Sham 69 gigs. As with any culture that grows into something big, morons join in along with everyone else and distort the original meaning. (An observation made again in Nirvana's "In Bloom" 20 years later, and by Robbie Williams roughly every other single.)

It's highly doubtful, of course, whether the film has even the remotest intention to make this point, but accidental meaning is a theme that crops up in "The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle" time and again. Almost three decades of hindsight lends the film a contemporary relevance and resonance that was almost certainly never intended by its makers. It starts, for example, with a Pop Idol-esque audition for a replacement singer for Rotten ("Kids Audition -Anyone Can Be A Sex Pistol", runs the billing) which was probably meant to be absurdly satirical rather than ending up as the most frighteningly prescient picture of the future since Orwell's "1984", but which is no less powerful for that.

But then, at the same time, the film also mimics quintessentially British culture like the gentle Ealing comedies, with veteran comic actresses like Irene Handl and 70s porn star Mary Millington lending their talents to segments that imply the entire film is tongue-in-cheek post-modern (before anyone had even heard of "post-modern") self-mockery, a music-hall farce that's personified by Steve Jones' playing of the central "character" in what passes for the movie's binding narrative. A natural actor (a bit like his namesake Vinnie would turn out to be decades later), Jones hams up his role as a leather-trenchcoated gumshoe with deadpan wit that seems to debunk any notion of the movie being taken seriously. (And just to reinforce that view - it is, let's not forget, a musical. The story of the most subversive cultural phenomenon since the Tolpuddle Martyrs is a musical.)

And there are also genuinely documentary elements to the film, with clips of real events (like the extraordinary scenes when a crowd of hymn-singing locals picketed outside a Pistols gig in Caerphilly, Wales) and interviews with real figures from the story - record company executives, local councillors and so on - which cast light on things from an angle widely ignored in the rewritten modern history of punk. McLaren's careful cutting of these clips to assist in his own particular telling of the tale means you always need to keep a big pinch of salt handy with relation to the context and chronology, but much of the footage manages to stand on its own merits and speak for itself.

Swindle can't decide all the way through whether it's trying to present a polemic on behalf of McLaren's "I am the master manipulator who cleverly meant it to happen this way all along" hijacking of reality, or just take the piss, and the struggle between the two conflicting sides - mirroring, probably unintentionally, the conflict at the core of the Pistols between Rotten's serious-minded cultural-revolutionary politics and Jones and Cook's "We're only here for the birds and beer" perspective - is all the more fascinating for it.

So that's the movie - a messy but always-watchable tangle of reality and fantasy, insult to history and insight into it at the same time, never to be taken at face value but nevertheless containing plenty of truth for the attentive viewer who can be bothered to look for it. What about the album? The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle soundtrack is a record that's almost never afforded any merit or significance at all when looking back at the legacy of the Sex Pistols, but it actually contains some of the most telling and candid representations of their existence, as well as pointers to the futures of the various protagonists.

Tracks like "Lonely Boy" and "Silly Thing", for example, while credited to the Pistols, are clearly the prototypes for the work of The Professionals, the band formed by Cook and Jones after the last remnants of the Pistols finally dissolved some time after the initial breakup. (Increasingly desperate cash-in "Sex Pistols" records, such as the posthumously-released Sid Vicious covers of 50s rock standards "C'mon Everybody" and "Something Else" and Ronnie Biggs' "No-one Is Innocent", continued to appear in a steady stream for years after the band disintegrated on stage at the Winterland in San Francisco at the end of their American tour in January 1978.) The Professionals (and the aforementioned Swindle tracks) pioneered a curious kind of "sensitive yob" rock, combining the trademark heavy Pistols sound with melancholy, regretful lyrics and singalong football-crowd choruses, which enjoyed minor chart success with great singles like "1-2-3", "Just Another Dream" and "Kick Down The Doors" but couldn't sustain the band beyond a patchy second LP in 1981.

And McLaren's own numbers, including orchestral takes on "EMI" and "God Save The Queen" (the latter of which he uses, via a whispered voiceover, to introduce the Fagin-esque character he attempts to portray himself as in the movie and set out the idea of "The Swindle" itself) and a rendition of music-hall standard "You Need Hands" (made famous by Max Bygraves) foreshadowed the eclectic directions he would go on to take in later years, touching on everything from the urban dance music of Soweto to the oddly moving opera-based single "Madam Butterfly". But in these five songs of McLaren, Cook and Jones (out of the album's 24) we've still only heard a fraction of Swindle's all-encompassing scope.

In addition to Cook and Jones' yob rock and McLaren's classical/theatrical dabblings, the album also reflects the movie's random balance between the whimsical and the unsavoury, featuring the contributions of Ronnie Biggs and "Martin Bormann", with the latter singing on one of two versions of the ugly, morally-ambiguous "Belsen Was A Gas" (Sid Vicious' only recorded songwriting credit in the band, and which in the hands of Rotten sounded like an anti-war anthem, but rather different coming supposedly from a Nazi war criminal with new lyrics). But there's also a couple of cartoon-punk numbers from Eddie Tenpole (later to form New Romantic village idiots Tenpole Tudor of "Swords Of A Thousand Men" fame) in the form of "Who Killed Bambi?" and a silly cover of "Rock Around The Clock".

(It's worth diverging momentarily at this point to note that "Who Killed Bambi?" was the movie's original title, and work had actually been started on filming a very different script - written, faintly amazingly, by the now-famous US movie critic Roger Ebert - before it became Swindle. All there was to show for the first £75,000 spent by McLaren and original director Russ "Valley Of The Dolls" Meyer was a sequence showing the nasty, and real, cold-blooded killing of a baby deer in a Welsh forest, which adorns the album's back cover lying dead in a pile of autumn leaves from a bloodstained crossbow-dart wound in its throat. Curiously, an unrelated French movie of the same title was released in 2003.)

We also get all three of Vicious' crude but entertaining solo efforts, including his valedictory yowl through "My Way". But in the eyes of the public the Sex Pistols were still synonymous with their frontman, and for the album to have any credibility as a Sex Pistols release McLaren needed to have a substantial presence from Rotten on it. Unfortunately for him, by 1979 the relationship between the manager and the former singer was poisoned beyond rescue (as indeed it remains to this day), and McLaren had to resort to desperate measures, tacking a load of cursory, slapdash 60s-rock covers recorded early in the Pistols career for B-sides onto the tracklisting, along with a version of "Anarchy In The UK" and a rehearsal-room tape that inadvertently provides Swindle's most affecting moment.

Forming the second and third tracks on the album, the recording has the Pistols (in the form of Rotten, Cook and Jones - who, if anyone, is playing bass guitar is unknown, but it doesn't seem to be either the inept Vicious or original, sacked, bassist Glen Matlock) messing around half-arsedly in the studio playing a cover of Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode". Rotten gets four tuneless, off-key words into the song before screwing it up ("If you could seeee... oh God, fuck off") but ploughs through the first verse before muttering "I dunno the words" and descending into improvised scat gibberish instead. This semi-entertains the singer for another minute or so before he complains "Stop it, it's fucking awful" and suggests they play "Road Runner" instead. The band segue without pausing into the classic Jonathan Richman number (giving the lie to McLaren's claims throughout the movie that they couldn't play), until Rotten laughs that he doesn't know the words to that one either.

But the others keep playing, and Rotten does his best around what lyrics he does know, seemingly just for something to do to relieve the monotony of this pointless busy-work exercise. No-one has ever sounded less convincing singing the words "Felt in touch with the modern world, fell in love with the modern world". Moments afterwards Rotten improvises the line "So cold here in the dark... with 50,000 watts of power", and the good-vibes driving song suddenly takes on an air of unfamiliar poignant melancholy.

This was a band being vilified in the entire world's press, physically attacked in the streets (McLaren's faux-Machiavellian recounting in the movie of his glee at Rotten being slashed by a gang of thugs outside a pub and Cook being beaten up and stabbed by a crowd in a tube station is one of the film's most genuinely distasteful parts), and generally presented as unspeakable evil Antichrists threatening the destruction of society as we know it, yet here they're revealed as a bored, ordinary and isolated bunch of young men aimlessly killing time in a grubby windowless room while other people manipulate their lives into a hideous mess, their famed and supposedly world-shattering music seemingly powerless to help them.

Dejectedly, the singer continues to bemoan the situation ("Road runner, road runner...oh God, I don't know it, it's fucking ridicularse... wish I had the words") as the others continue doggedly on. As Rotten appears to give up entirely, the band build the song up to a climax, a crash of Cook's cymbals seems to fire the singer to one last effort and he suddenly throws his heart into it just when it seems hopeless - "...runner, Road RUNNER" and suddenly it's the old familiar Rotten, spitting life and bile into these most easy-going of lyrics and summoning up everything he can pull together to try to give this bleak situation some meaning and purpose. It only lasts about 20 thrilling seconds, as the singer's lack of command of the words leaves him with nowhere to go and the song stumbles to an untidy close, but for those few seconds "Road Runner" is nothing less than a shining demonstration of the magical capabilities of music, as a room full of people who don't like each other, stuck in a miserable situation to produce a filler track on a cynical cash-in album, somehow combine to make something that's an uplifting affirmation of the uniqueness of humanity and its capacity to create works of power and beauty at the unlikeliest moments.

Immediately after this, we get another of the album's many musical highpoints, in the form of the Black Arabs' eponymous disco medley. Funky wah-wah guitar and a throbbing hi-energy beat underpin a Boney M-style melding of "Anarchy", "God Save The Queen", "Pretty Vacant" and, oddly, Biggs' "No-one Is Innocent" - the lack of distinction between the "real" Pistols and the cash-in circus redolent of Swindle's kitchen-sink philosophy.

But even now we're not done with digging gems out of the album's random car-boot-sale collection of passingly-Sex-Pistols-related music. After some more Rotten covers and Cook and Jones numbers, we get a French-busker-with-accordion rendition of "Anarchie Pour l'UK" which shows what a great tune it is even when stripped of the Pistols' distinctive sonic assault. (This is a point, incidentally, that's also illustrated by many subsequent covers by various artists, including a lovely Waterboys-like acoustic version on the little-known "The Swindle Continues" album released by former Pistols soundman Dave Goodman, supposedly in collaboration with Cook and Jones, in 1988.) It also sounds a lot better when heard on the album, removed from the scenes of Vicious acting like an ignorant cretin in Paris which it's used to soundtrack in the movie.

And then, after a five-track Vicious/"Bormann"/Biggs cabaret interlude, and McLaren's orchestral, self-voiced reinterpretation of "EMI", it's time for the theme song.

"The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle" itself, written by Cook and Jones with the movie's director Julian Temple and sung by Eddie Tenpole and a load of singer-audition hopefuls, is one of the great unacclaimed punk singles. Setting out its stall immediately with the opening couplet "People said we couldn't play, they called us foul-mouthed yobs/But the only notes that really count are the ones that come in wads", this is a theme song in the most literal sense, summarising the movie's plot and the band's history in three slogan-strewn minutes of gloating about all the money McLaren has (supposedly) deliberately and cunningly embezzled from the music business, before Tenpole embarks on an extended and improvised libellous attack on various rock dinosaurs and punk contemporaries - Elvis Presley ("Died in 1959"), Chuck Berry, Ian Dury ("Cockney fraud"), Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan ("A parking ticket stuck to his arsehole"), Rod Stewart - and then the members of the Pistols themselves ("Sid Vicious, rock'n'roll clich-eye") over the triumphant guitar chords and the joyous refrain of the chorus line.

Eventually Tenpole dissolves into incoherent ranting and the wannabe Sex Pistols Idols come back in, chanting "Rock'n'roll swindle" in turn until the song judders to a close. The last hopeful sneers "Swindle - it's a swindle!" as the final note dies away - an ironic echo, intended or not, of Rotten's "Ever get the feeling you've been cheated?" parting shot from the stage at the end of the Pistols' ill-fated gig at Winterland. (It may or may not be by chance that the track follows close on the heels of Vicious' "My Way", which features parting shots of another kind.)

It's a thrilling conclusion, but such a neat ending would be out of keeping with the tone and spirit of the rest of the album and movie, so we get McLaren's wildly-misplaced "You Need Hands" before the album's actual closing track, "Friggin' In The Riggin'", a traditional old salty sea shanty appropriated by Steve Jones with even fouler lyrics than usual and used to soundtrack the film's end/credits sequence which depicts the Pistols once again in cartoon form as the crew of a becalmed, but then increasingly storm-tossed, pirate ship, deserted by one member after another until only McLaren remains, saluting with a smile at the mast as the ship sinks beneath the waves and the song fades out to its cheerfully-nihilist refrain (Friggin' in the riggin', there was fuck-all else to do").

There's one last twist, though, as this "happy ending" for the album gives way in the film to a montage of newspaper clippings reporting Vicious' death from a heroin overdose while on bail for the alleged knife murder of his girlfriend Nancy Spungen in New York's Chelsea Hotel, the montage soundtracked only by the desolate squawking of a few unseen seagulls. The injection of such a sour note at the end, the movie clashing awkwardly with its own soundtrack, is typical of Swindle: a schizophrenic, amoral mess of a venture whose moments of redemption seem as deliberate - and simultaneously as incidental and unplanned - as its moments of crass offensiveness and cynical, one-sided character assassination.

In a world where spin-doctors, concentrated media ownership, the erosion of civil liberties in the name of fighting "terrorism", the cult of celebrity and 24-hour news analysis rob us of the opportunity to interpret events or culture for ourselves, Swindle's shrugged-shoulders confusion of morality forces the viewer/listener to actually think for themselves about what's being presented to them. It's a habit that's being gradually discouraged in 21st-Century society, and anything that helps to hold back that tide should be cherished and protected.

The movie works best when viewed in the context of the whole of the Sex Pistols history - particularly "The Filth And The Fury", which is seen by some as Julian Temple's apology to the band for their portrayal in Swindle - but stands up in its own right too, both as documentary (though not in the way McLaren intended it) and entertainment. For anyone to whom punk is some distant, abstract thing that happened before they were born, it's actually a pretty decent depiction of the atmosphere of the time (from the cultural, rather than political, perspective at least).